Opinion: Graffiti is art, not vandalism

February 20, 2020

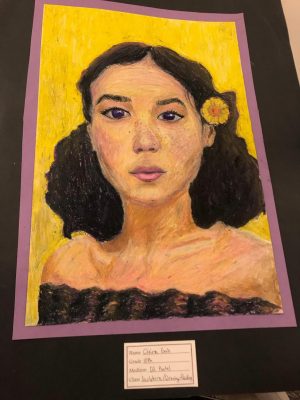

While walking down the streets of the northeast side of Flint, through the boarded, burnt and barren houses, a passerby may notice the plethora of street art lining the roads and buildings. Portraits of Frieda, murals of children and families, classic graffiti and more bring color and life into Flint’s atmosphere. This is a perfect example of how graffiti is not vandalism, but a valuable form of art.

Dating all the way back to the Pompeii era (according to Udemy professional learning platform), graffiti has been a way for people to communicate and express themselves for practically eons. Even the Maya Civilization drew photos on the walls to communicate, using glyphs instead of traditional text. Graffiti has been relied upon for centuries as a form of expression— and it is in the modern era, too.

Graffiti is, simply put, a key component of urban culture. Where would Flint, Detroit, Chicago, or any other urban city be without the pure creativity lining its cityscape? Well, it would be lifeless, colorless, and almost cultureless. Graffiti font is nearly a trademark; it defines urban style and ideas. Without it, the world’s cities simply would not be the same.

Apart from being imperative to an entire city’s culture, graffiti has given rise to a number of acclaimed artists. Banksy, Invader, JR and Swoon are all well-known street artists that go by a pseudonym, presumably to avoid legal repercussions (according to Timeout New York newsmagazine). Not all artists stick with street art, however. Andy Warhol’s “pop-art” style was even inspired by the graffiti he saw growing up. Jean-Michel Basquiat took it a step further by emulating Warhol’s style in actual graffiti, The Guardian Newspaper said. The world would be void of a number of great artists without graffiti.

As far as the law goes, Legal Match said that “any act of scratching, etching, painting, or other form of writing/drawing on the surface of someone else’s property” is considered vandalism, and graffiti usually falls under this category. That being said, a guilty vandalism charge could leave someone with jail time, fines, community service or more, which is why many famous street artists are forced to create masterpieces anonymously or under fake names, unable to take pride in the art that they slave over.

Many would argue that graffiti is vandalism, and that these artists should receive penalties for damaging other people’s property— but is graffiti really damage? When a train passes by, those in the stopped cars admire the paintings on the train cars; they don’t cringe at the “damage.” When walking through downtown Detroit, people take photos in front of the bright paintings. Graffiti is not damage, it’s beautiful, and it should be treated as such.

Peep • Dec 2, 2021 at 5:17 PM

agreeeeeeed

michael warda • Feb 22, 2020 at 6:42 AM

BRAVO